Event loop in JavaScript

Posted on February 1, 2016There are only two kinds of languages: the ones people complain about and the ones nobody uses. — Bjarne Stroustrup

Preface

This can be a long article, even tedious. It’s caused by a topic of process.nextTick. Javascript developer may face to setTimeout, setImmediate, process.nextTick everyday, but what the difference between them? Some seniors can tell:

- setImmediate is lack of implementations on browser side, only high-versioned Internet Explorer make sense.

- process.nextTick is triggered first,setImmediate sometimes comes last.

- Node environment has implemented all of the APIs.

At the very beginning, I’ve tried to search answers from Node official docs,and other articles. But unfortunately, I couldn’t access the truth. Other explaination can be found in reddit blackboard, 1, 2 and the author of Node wrote an article try to explain the logics.

I can not tell how many people know the truth and want to explore it, if you know more information, please contact me, I’m waiting for more useful information.

This article is not only about event loop, but also something like Non-blocking I/O. The first thing I want to say is about I/O Models.

I/O Models

Operating System’s I/O Models can be divided into five categories: Blocking I/O, Non-blocking I/O, I/O Multiplexing, Signal-driven I/O and Asynchronous I/O. I will take Network I/O case for example, though there still have File I/O and other types, such as DNS relative and user code in Node. Take Network scenario as an example is just for convenience.

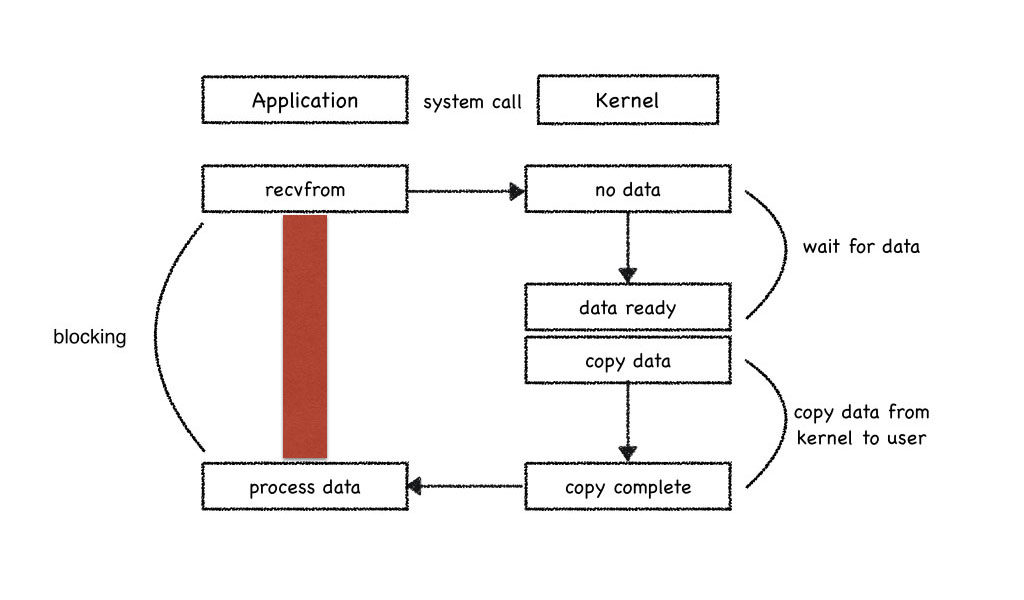

Blocking I/O

Blocking I/O is the most common model but with huge limitation, obviously it can only deal with one stream (stream can be file, socket or pipe). Its flows diagram demonstrated below:

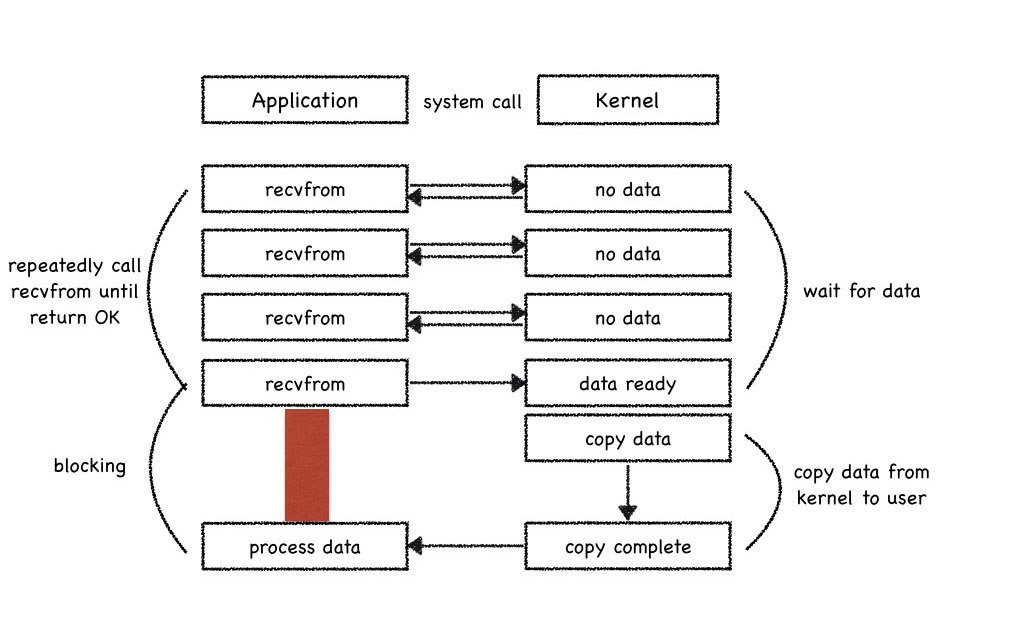

Non-Blocking I/O

Non-Blocking I/O, AKA busy looping, it can deal with multiple streams. The application process repeatedly call system to get the status of data, once any stream’s data becomes ready, the application process block for data copy and then deal with the data available. But it has a big disadvantage for wasting CPU time. Its flows diagram sdemonstrated below:

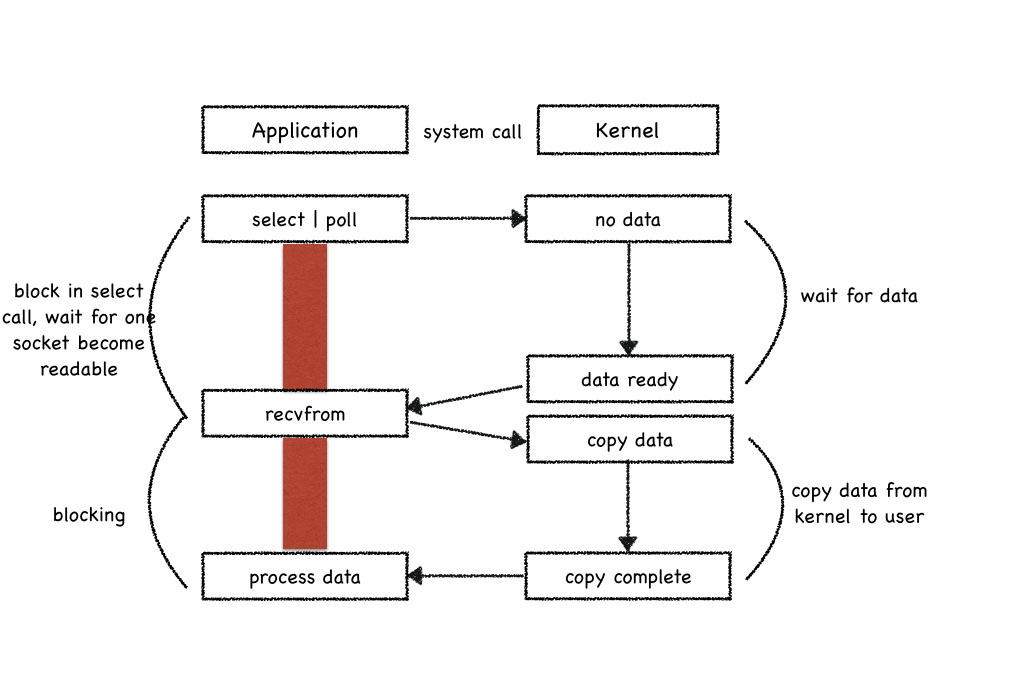

I/O Multiplexing

Select and poll are based on this type, see more about select and poll. I/O Multiplexing retains the advantage of Non-Blocking I/O, it can also deal with multiple streams, but it’s also one of the blocking types. Call select (or poll) will block application process until any stream becomes ready. And even worse, it introduce another system call (recvfrom).

Notes: Another closely related I/O model is to use multi-threading with blocking I/O. That model very closely resembles the model described above, except that instead of using select to block on multiple file descriptors, the program uses multiple threads (one per file descriptor), and each thread is then free to call blocking system calls like recvfrom.

Its flows diagram demonstrated below:

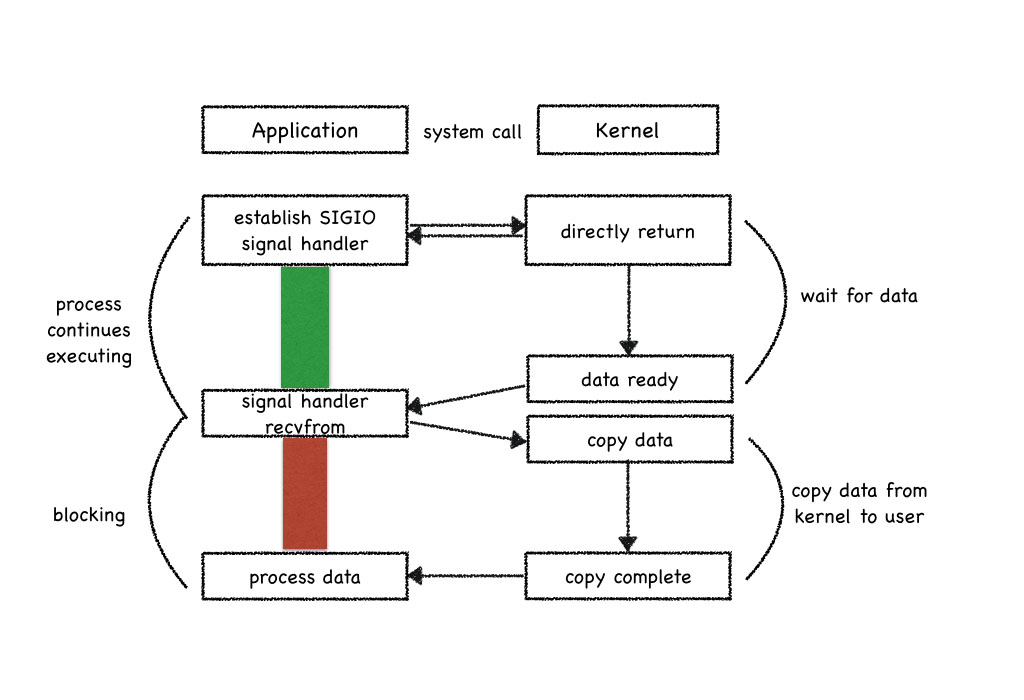

Signal-driven I/O

In this model, application process system call sigaction and install a signal handler, the kernel will return immediately and the application process can do other works without being blocked. When the data is ready to be read, the SIGIO signal is generated for our process. We can either read the data from the signal handler by calling recvfrom and then notify the main loop that the data is ready to be processed, or we can notify the main loop and let it read the data. Its flows diagram demonstrated below:

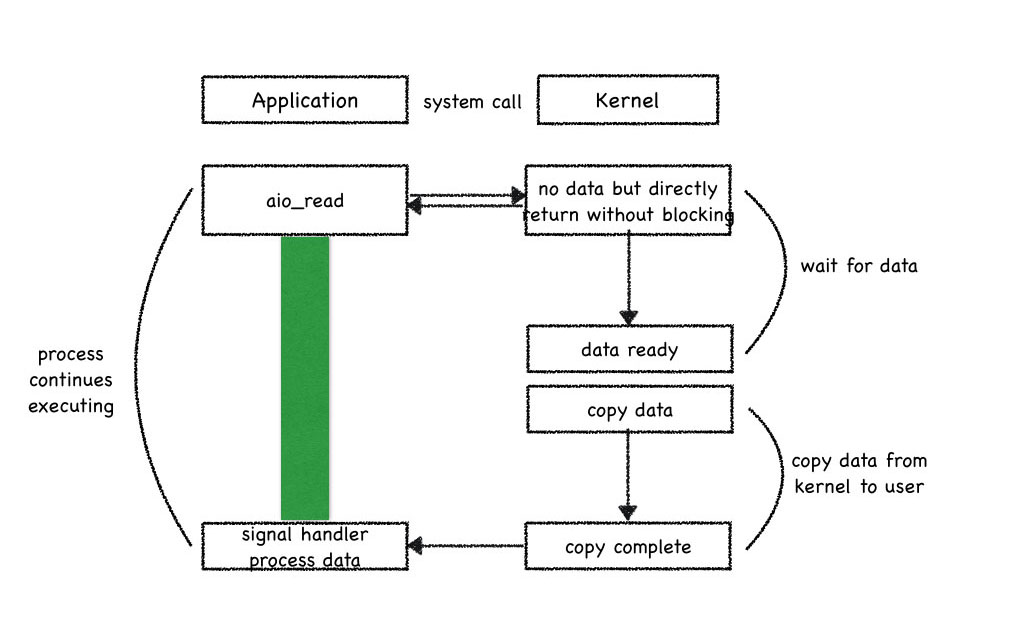

Asynchronous I/O

Asynchronous I/O is defined by the POSIX specification, it’s an ideal model. In general, system call like aio_* functions work by telling the kernel to start the operation and to notify us when the entire operation (including the copy of the data from the kernel to our buffer) is complete. The main difference between this model and the signal-driven I/O model in the previous section is that with signal-driven I/O, the kernel tells us when an I/O operation can be initiated, but with asynchronous I/O, the kernel tells us when an I/O operation is complete. Its flows demonstrated below:

After introduced those type of I/O models, we can identify them with the current hot-spots technologies such as epoll in linux and kqueue in OSX. They’re more like the I/O multiplexing model, only the IOCP on windows implement the fifth model. See more: from zhihu.

Then have a look at libuv, an I/O library written in C++.

libuv

libuv is one of the dependencies of Node, another is well-known v8. libuv take care of different I/O model implementations on different Operating System and abstract them into one API for third-party application. libuv has a brother called libev, which appears earlier than libuv, but libev didn’t support windows platform. This becomes more and more important while Node becomes more and more popular so that they must consider of windows compatibility. At last Node development team give up libev and pick up libuv instead.

Before we read more about libuv, I should make a tip, I have read many articles and guides who introduce the event loop in JavaScript, and they seem no much more difference. I think those authors mean to explain the conception as easy as possible and most of them do not show the source code of Webkit or Node. Many readers forget how the event loop schedule asynchronous tasks and face to the same problem when they encounter it again.

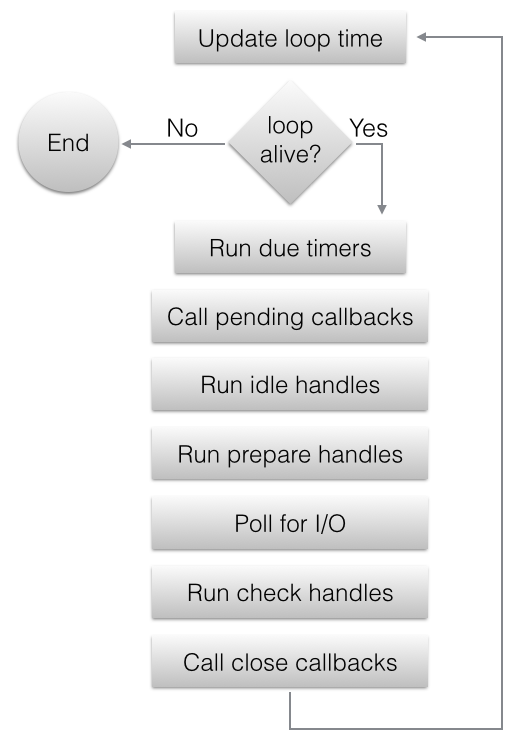

First I want to differ the conceptions of event loop and event loop iteration. Event loop is a task queue which bind with a single thread, they are one-to-one relation. Event loop iteration is the procedure when the runtime check for task (piece of code) queued in event loop and execute it. The two conceptions map tp two important function / object in libuv. One is uv_loop_t, which represent for one event loop object and API: uv_run , which can be treated as the entry point of event loop iteration. All functions in libuv named starts with uv_, which really make reading the source code easy.

uv_run

The most important API in libuv is uv_run, every time call this function can do an event loop iteration. uv_run code shows below (based on implementation of v1.8.0):

int uv_run(uv_loop_t* loop, uv_run_mode mode) {

int timeout;

int r;

int ran_pending;

r = uv__loop_alive(loop);

if (!r)

uv__update_time(loop);

while (r != 0 && loop->stop_flag == 0) {

uv__update_time(loop);

uv__run_timers(loop);

ran_pending = uv__run_pending(loop);

uv__run_idle(loop);

uv__run_prepare(loop);

timeout = 0;

if ((mode == UV_RUN_ONCE && !ran_pending) || mode == UV_RUN_DEFAULT)

timeout = uv_backend_timeout(loop);

uv__io_poll(loop, timeout);

uv__run_check(loop);

uv__run_closing_handles(loop);

if (mode == UV_RUN_ONCE) {

/**

* UV_RUN_ONCE implies forward progress: at least one callback

* must have been invoked when it returns. uv__io_poll() can return

* without doing I/O (meaning: no callbacks) when its timeout

* expires - which means we have pending timers that satisfy

* the forward progress constraint.

*

* UV_RUN_NOWAIT makes no guarantees about progress so it's

* omitted from the check.

*/

uv__update_time(loop);

uv__run_timers(loop);

}

r = uv__loop_alive(loop);

if (mode == UV_RUN_ONCE || mode == UV_RUN_NOWAIT)

break;

}

/**

* The if statement lets gcc compile it to a conditional store. Avoids

* dirtying a cache line.

*/

if (loop->stop_flag != 0)

loop->stop_flag = 0;

return r;

}Every time runtime do an event loop iteration, it executes the ordered code as figure below, and we can know what kind of callbacks would be called during each event loop iteration.

As libuv described the underline principle, timer relative callbacks will be called in the uv__run_timers(loop) step, but it don’t mention about setImmediate and process.nextTick. It’s reasonable obviously, libuv is lower layer of Node, so logic in Node will be taken account in itself (more flexible). After diving into the source code of Node project, we can see what happened when setTimeout/setInterval, setImmediate and process.nextTick.

Node

Node is a popular and famous platform for JavaScript, this article don’t cover any primary technology about Node which you can find in any other technical books. If you want to, I’m willing to recommend you Node.js in Action and Mastering Node.js.

All Node source code shown in this article based on v4.4.0 (LTS).

Setup

When setup a Node process, it also setup an event loop. See the entry method StartNodeInstance in src/node.cc, if event loop is alive the do-while loop will continue.

bool more;

do {

v8::platform::PumpMessageLoop(default_platform, isolate);

more = uv_run(env->event_loop(), UV_RUN_ONCE);

if (more == false) {

v8::platform::PumpMessageLoop(default_platform, isolate);

EmitBeforeExit(env);

// Emit `beforeExit` if the loop became alive either after emitting

// event, or after running some callbacks.

more = uv_loop_alive(env->event_loop());

if (uv_run(env->event_loop(), UV_RUN_NOWAIT) != 0)

more = true;

}

} while (more == true);Async user code

setTimeout

Timers are crucial to Node.js. Internally, any TCP I/O connection creates a timer so that we can time out of connections. Additionally, many user user libraries and applications also use timers. As such there may be a significantly large amount of timeouts scheduled at any given time. Therefore, it is very important that the timers implementation is performant and efficient.

In Node, definition of setTimeout and setInterval locate at lib/timer.js. For performance, timeout objects with their timeout value are stored in a Key-Value structure (object in JavaScript), key is the timeout value in millisecond, value is a linked-list contains all the timeout objects share the same timeout value. It used a C++ handle defined in src/timer_wrap.cc as each item in the linked-list. When you write the code setTimeout(callback, timeout), Node initialize a linked-list(if not exists) contains the timeout object. Timeout object has a _timer field point to an instance of TimerWrap (C++ object), then call the _timer.start method to delegate the timeout task to Node. The snippet from lib/timer.js, when called setTimeout in JavaScript it new a TimersList() object as a linked-list node and store it in the Key-Value structure.

function TimersList(msecs, unrefed) {

// Create the list with the linkedlist properties to

this._idleNext = null;

// prevent any unnecessary hidden class changes.

this._idlePrev = null;

this._timer = new TimerWrap();

this._unrefed = unrefed;

this.msecs = msecs;

}

// code ignored

list = new TimersList(msecs, unrefed);

// code ignored

list._timer.start(msecs, 0);

lists[msecs] = list;

list._timer[kOnTimeout] = listOnTimeout;Notice the constructor of TimersList, it initialize a TimerWrap object, which build its handle_ field, a uv_timer_t object. The snippet from src/timer_wrap.cc show that:

static void Initialize(Local<Object> target,

Local<Value> unused,

Local<Context> context) {

// code ignored

env->SetProtoMethod(constructor, "start", Start);

env->SetProtoMethod(constructor, "stop", Stop);

}

static void New(const FunctionCallbackInfo<Value>& args) {

// code ignored

new TimerWrap(env, args.This());

}

TimerWrap(Environment* env, Local<Object> object)

: HandleWrap(env,

object,

reinterpret_cast<uv_handle_t*>(&handle_),

AsyncWrap::PROVIDER_TIMERWRAP) {

int r = uv_timer_init(env->event_loop(), &handle_);

CHECK_EQ(r, 0);

}Then the TimerWrap designate the timeout task to its handle_. The workflow is simple enough that Node do not take care of what time exactly the timeout callback get called, it all depends on libuv’s timetable. We can see it in the Start method of TimerWrap (called from client javascript code), it invoke uv_timer_start to schedule the timeout callback.

static void Start(const FunctionCallbackInfo<Value>& args) {

TimerWrap* wrap = Unwrap<TimerWrap>(args.Holder());

CHECK(HandleWrap::IsAlive(wrap));

int64_t timeout = args[0]->IntegerValue();

int64_t repeat = args[1]->IntegerValue();

int err = uv_timer_start(&wrap->handle_, OnTimeout, timeout, repeat);

args.GetReturnValue().Set(err);

}Back to the figure above in libuv section, you can find in each event loop iteration, event_loop can schedule the timeout task itself, with update the time of event_loop, it can accurately know when to execute the OnTimeout callback of TimerWrap. Which can invoke the bound javascript functions.

static void OnTimeout(uv_timer_t* handle) {

TimerWrap* wrap = static_cast<TimerWrap*>(handle->data);

Environment* env = wrap->env();

HandleScope handle_scope(env->isolate());

Context::Scope context_scope(env->context());

wrap->MakeCallback(kOnTimeout, 0, nullptr);

}Dive into libuv source code, every time uv_run invoke uv__run_timers(loop), which defined in deps/uv/src/unix/timer.c, it compares the timeout of uv_timer_t and time of event_loop, if they hit each other then execute the callbacks.

void uv__run_timers(uv_loop_t* loop) {

struct heap_node* heap_node;

uv_timer_t* handle;

for (;;) {

heap_node = heap_min((struct heap*) &loop->timer_heap);

if (heap_node == NULL)

break;

handle = container_of(heap_node, uv_timer_t, heap_node);

if (handle->timeout > loop->time)

break;

uv_timer_stop(handle);

uv_timer_again(handle);

handle->timer_cb(handle);

}

}Notice about the uv_timer_again(handle) code above, it differs the setTimeout and setInterval, but the two APIs invoke the same functions underline.

setImmediate

Node did most of the same job with setTimeout when you write javascript code as setImmediate(callback). Definition of setImmediate is also in lib/timer.js, when call this method it will add private property _immediateCallback to process object so that C++ bindings can identify the callbacks’ proxy registered, and finally return an immediate object (you can think it as another timeout object but without timeout property). Internally, timer.js maintain an array named immediateQueue, which contains all callbacks installed in current event loop iteration.

exports.setImmediate = function(callback, arg1, arg2, arg3) {

// code ignored

var immediate = new Immediate();

L.init(immediate);

// code ignored

if (!process._needImmediateCallback) {

process._needImmediateCallback = true;

process._immediateCallback = processImmediate;

}

if (process.domain)

immediate.domain = process.domain;

L.append(immediateQueue, immediate);

return immediate;

};Before Node setup an event loop, it build an Environment object (Environment class definition locates in src/env.h) which shared by all current process code. See the method CreateEnvironment in src/node.cc. CreateEnvironment setup an uv_check_t used by its event loop. Snippet showed that.

Environment* CreateEnvironment(Isolate* isolate,

uv_loop_t* loop,

Local<Context> context,

int argc,

const char* const* argv,

int exec_argc,

const char* const* exec_argv) {

// code ignored

uv_check_init(env->event_loop(), env->immediate_check_handle());

uv_unref(

reinterpret_cast<uv_handle_t*>(env->immediate_check_handle()));

// code ignored

SetupProcessObject(env, argc, argv, exec_argc, exec_argv);

LoadAsyncWrapperInfo(env);

return env;

} Method SetupProcessObject defined in src/node.cc, this can make global process object have necessary bindings. From code below we can find that it assign an set accessor by calling need_imm_cb_string() to the NeedImmediateCallbackSetter method. If we had a look at src/env.h, we know that need_imm_cb_string() return the string: “_needImmediateCallback”. This means every time javascript code set an “_needImmediateCallback” property on process object, NeedImmediateCallbackSetter will get called.

void SetupProcessObject(Environment* env,

int argc,

const char* const* argv,

int exec_argc,

const char* const* exec_argv) {

// code ignored

maybe = process->SetAccessor(env->context(),

env->need_imm_cb_string(),

NeedImmediateCallbackGetter,

NeedImmediateCallbackSetter,

env->as_external());

// code ignored

} In method NeedImmediateCallbackSetter it start the uv_check_t handle if process._needImmediateCallback is set to true, which managed by libuv’s event loop (env->event_loop()), and initialized in CreateEnvironment method.

static void NeedImmediateCallbackSetter(

Local<Name> property,

Local<Value> value,

const PropertyCallbackInfo<void>& info) {

Environment* env = Environment::GetCurrent(info);

uv_check_t* immediate_check_handle = env->immediate_check_handle();

bool active = uv_is_active(

reinterpret_cast<const uv_handle_t*>(immediate_check_handle));

if (active == value->BooleanValue())

return;

uv_idle_t* immediate_idle_handle = env->immediate_idle_handle();

if (active) {

uv_check_stop(immediate_check_handle);

uv_idle_stop(immediate_idle_handle);

} else {

uv_check_start(immediate_check_handle, CheckImmediate);

// Idle handle is needed only to stop the event loop from blocking in poll.

uv_idle_start(immediate_idle_handle, IdleImmediateDummy);

}

}At last, we dive into CheckImmediate, notice the immediate_callback_string method will return string: “_immediateCallback”, that we have seen in timer.js.

static void CheckImmediate(uv_check_t* handle) {

Environment* env = Environment::from_immediate_check_handle(handle);

HandleScope scope(env->isolate());

Context::Scope context_scope(env->context());

MakeCallback(env, env->process_object(), env->immediate_callback_string());

}So we knew that, in every event loop iteration, setImmediate callbacks would be executed in the uv__run_check(loop); step followed uv__io_poll(loop, timeout);. If get a little confused, you can back to the diagram in event loop iteration execute order.

process.nextTick

process.nextTick might have the ability to hide its implementation ^_^. I have issued that for node project to get more information. At last I closed it myself because I thought the author got a little confused about my question. Debug into the source code also make sense, I add logs in the source code and recompiled the whole project to see what happened.

The entry point is in src/node.js, there is a processNextTick method that build the process.nextTick API. process._tickCallback is the callback function must be executed properly by C++ code (or if you use require('domain') it would be override by process._tickDomainCallback). Every time you called process.nextTick(callback) from your javascript code, it maintains nextTickQueue and tickInfo objects for recording necessary tick information.

process._setupNextTick is another important method in src/node.js, it map to a C++ binding Function named SetupNextTick in src/node.cc. In this method, it take the first argument and set it the tick_callback_function as a Persistent

// This tickInfo thing is used so that the C++ code in src/node.cc

// can have easy access to our nextTick state, and avoid unnecessary

// calls into JS land.

const tickInfo = process._setupNextTick(_tickCallback, _runMicrotasks);

function _tickCallback() {

var callback, args, tock;

do {

while (tickInfo[kIndex] < tickInfo[kLength]) {

tock = nextTickQueue[tickInfo[kIndex]++];

callback = tock.callback;

args = tock.args;

// Using separate callback execution functions allows direct

// callback invocation with small numbers of arguments to avoid the

// performance hit associated with using `fn.apply()`

_combinedTickCallback(args, callback);

if (1e4 < tickInfo[kIndex])

tickDone();

}

tickDone();

_runMicrotasks();

emitPendingUnhandledRejections();

} while (tickInfo[kLength] !== 0);

}And snippet in SetupNextTick method from node.cc showed that env object will get a tick_callback_function passed from arguments to be the callback when current tick transmitting to next phrase.

env->SetMethod(process, "_setupNextTick", SetupNextTick);

void SetupNextTick(const FunctionCallbackInfo<Value>& args) {

Environment* env = Environment::GetCurrent(args);

CHECK(args[0]->IsFunction());

CHECK(args[1]->IsObject());

env->set_tick_callback_function(args[0].As<Function>());

env->SetMethod(args[1].As<Object>(), "runMicrotasks", RunMicrotasks);

// Do a little housekeeping.

env->process_object()->Delete(

env->context(),

FIXED_ONE_BYTE_STRING(args.GetIsolate(), "_setupNextTick")).FromJust();

// code ignored

args.GetReturnValue().Set(Uint32Array::New(array_buffer, 0, fields_count));

}So we just need to search when the tick_callback_function() get called. After a while I find that env()->tick_callback_function() can be called from two places. First is the Environment::KickNextTick defined in src/env.cc. It called by node::MakeCallback in src/node.cc, which is only called by API internally. Second is AsyncWrap::MakeCallback defined in src/async_wrap.cc. It’s also the same as the author mentioned that, only the AsyncWrap::MakeCallback can be called by public.

I have added some logs to see what happened internally. Only know the callbacks run at the end phase of each event loop is not enough for me. At last I find that every AsyncWrap is a wrapper for async operations, the TimerWrap inherited from AsyncWrap. When timeout handler execute the callback OnTimeout, it actually execute the AsyncWrap::MakeCallback. You can see the same code showed before in the setTimeout section:

static void OnTimeout(uv_timer_t* handle) {

TimerWrap* wrap = static_cast<TimerWrap*>(handle->data);

Environment* env = wrap->env();

HandleScope handle_scope(env->isolate());

Context::Scope context_scope(env->context());

wrap->MakeCallback(kOnTimeout, 0, nullptr);

}A dark day seems bright now, every stage in uv_run can be the last stage of event loop iteration, such like timeout, it check and execute the env()->tick_callback_function(). Another API setImmediate ended in the internal called node::MakeCallback, node does the same work. And the last part of StartNodeInstance, EmitBeforeExit(env) and EmitExit(env) will also call the node::MakeCallback to ensure the tick_callback_function can be called before process exit.

File I/O

Not yet finished, coming soon…

Network I/O

Not yet finished, coming soon…

Quiz

You can now take a quiz to test whether you have already understand the event loop in Node.js totally. It mainly contains user asynchronous code. Have a try.

Conclusion

When called setTimeout and setImmediate, it schedules the callback function as a task to be executed in next event loop iteration. But nextTick won’t. It will get called before current event loop iteration ended. Also we can foresee that if we called the nextTick recursively the timeout task have no chance to execute during such procedure.

References

[1] understanding-the-nodejs-event-loop/

[2] introduction/unix-network-programming-v1.3

[3] the-event-loop-and-non-blocking-io-in-node-js

[4] the-style-of-non-blocking

[5] understanding-the-node-js-event-loop

[6] concurrency-vs-parallelism-what-is-the-difference

[7] asynchronous-disk-io

[8] understanding-the-javascript-event-loop

[9] linux-patches/nio-improve

[10] libuv design document